Ya-Chieh Hsu: Running a Candy Shop (Part 1)

How do you develop a new model of the way the body organizes itself while dealing with the challenges of starting your own lab? Dr. Ya-Chieh Hsu, an assistant professor at Harvard studying skin regeneration, did just that. We spoke with Dr. Hsu about her journey from high school research student to principal investigator.

Dr. Ya-Chieh Hsu.

Q: To kick things off, tell us a bit about what your labis working on.

A: We have a strong interest in understanding the biology of transit-amplifying cells. They are generated by stem cells to produce downstream tissues. Many somatic stem cells are in a dormant state. By contrast, transit-amplifying cells are the major workforce for homeostasis, repair, and regeneration. They are the cells that amplify the tissues and generate diverse cell types downstream. Defects in transit-amplifying cells lead to failure in tissue production. Due to transit-amplifying cells’ highly proliferative nature, they are also the cells destroyed upon chemotherapy. However, since the field has been very “stem cell centric,” we know very little about them.

Using hair follicles as our model, we have discovered, and continue to be fascinated by, the diverse functions of transit-amplifying cells. We realized that these cells regulate both stem cells and likely a wide variety of cell types in the niche. In this sense, transit-amplifying cells function as the key communicator to coordinate stem cell input, differentiated cell output, and niche changes. They are like the “go-to” person in an organization that everybody is dependent upon! We are very interested in learning more about their multifaceted nature and think this will provide a solid background for understanding the damage caused by transit-amplifying cell destruction, like in chemotherapy patients.

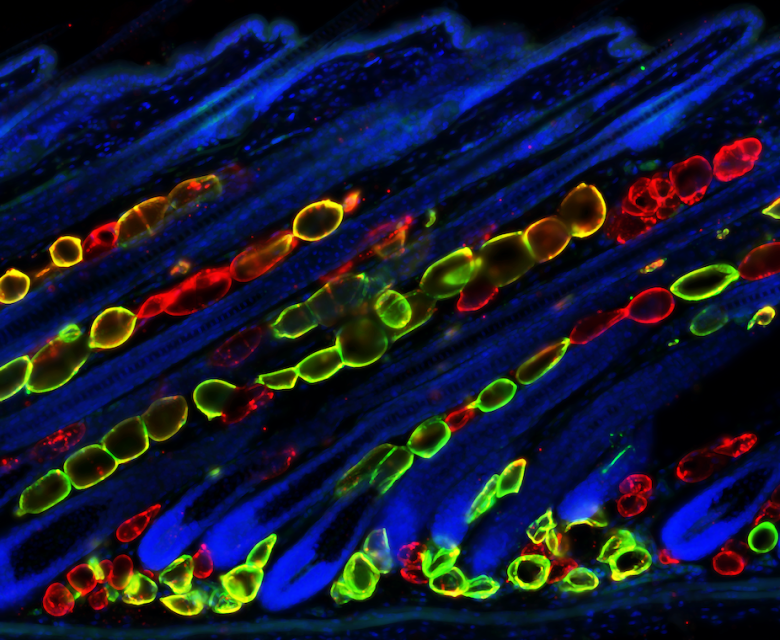

Transit-amplifying cells of one tissue (the hair follicles) can govern the production of a surrounding tissue (the adipocytes). Newly generated adipocytes are in red. See the paper for details.

Q: Starting a new lab is exciting. Today, there are lots of postdocs and graduate students who don't really know how interested they might be in leading their own academic lab. What would you say to these people who might be unsure about pursuing an academic role?

A: When I first encountered science, I was like a kid in a candy shop, and that never really changed. At the end of the day, my passion for science is still what drives me. If I keep that analogy, running my own lab perhaps is more like running a candy shop for the other kids! Liking candy is important, but of course, running a candy shop requires different skills. I was nerdy enough to want to be a scientist since I was first exposed to the scientific discovery process in high school. I was completely hooked – I didn't even know that such a career option existed!

When I first encountered science, I was like a kid in a candy shop, and that never really changed. At the end of the day, my passion for science is still what drives me.

However, that doesn't mean I was aware of what it takes to run a lab. In fact, I remained relatively naive about this until perhaps mid-way through my postdoc, which I don’t necessarily think is a bad thing. This “naiveness” lightened up a lot of worries. I just knew that I couldn’t wait to get to know the results day in and day out. I loved thinking about science projects and discussed findings with other scientists. I loved teaching and mentoring junior scientists. I even liked the process of sitting in front of the computer screen pulling out my hair to craft the papers/reviews/grants that I was writing. At the end, it turns out that there is only one career on earth that will enable me to do all of these – which is the one I have!

It’s important to pursue a career that fits your talents and passion. If you like science, there are many ways to contribute to it, and none of them are less important than running an academic lab – we need exceptional editors, reporters, science policy-makers, teachers, as well as scientists at all levels in both academic and industry, just to name a few. If any of these careers are better suited for you, go for them!

For those who have an interest in leading their own academic lab but are unsure because it seems so hard and the opportunities look so slim – I am going to borrow what Anne Lamott said in her book Bird by Bird: “It is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” It is perfectly normal to feel uncertain, anxious, and discouraged from time to time. However, if leading a lab somehow feels like the right aspiration for you, go for it. Focus on doing the best possible science and never compromise on your standard. Grab all the opportunities to learn and grow continuously. Force yourself out of your own comfort zones. If you focus on the important things, the rest will somehow take care of itself. It will definitely be hard, and it will be challenging, but it will also be a lot of fun.

If leading a lab somehow feels like the right aspiration for you, go for it. Focus on doing the best possible science and never compromise on your standard.

Q: Why did you decide to come to the US to pursue your PhD and what were the challenges associated with it?

A: I was attracted to the plethora of scientific opportunities available in the US. In addition, I had just graduated from college at that time. At that point in life, you just want to see the world you haven’t seen before! The biggest challenges I faced are shared among many international students: language, culture, and the physical distance from my family. The first two challenges get better, but the third one, in fact, becomes more difficult with time.

The influence of language and culture are profound. I personally found the adjustment experience a valuable one. The struggles I had, the sense of disconnect and not belonging, the restraints of not being able to express oneself freely. The misunderstandings. These experiences were not pleasant, but they enriched my life. One “benefit” was that I noticed I was able to develop a very thick skin very quickly, in part through these experiences – you quickly learn that you can’t always care what people think of you, or care if you’re misunderstood, because it happens all the time!

The biggest challenges I faced are shared among many international students: language, culture, and the physical distance from my family. The first two challenges get better, but the third one, in fact, becomes more difficult with time.

Still, I have always wondered if there might be a way to bring more awareness and more sensitivity to the difficulties that international students might be facing. I don’t think there are any easy answers, since science relies heavily on good communication, which involves both language and culture. But being a bit more sympathetic and open-minded can help. After all, other than certain shared core values and standards, there are many different ways of working in science.

Q: Who were or who are your role models? How would you suggest people find the right role models in their careers?

A: In a way, all the mentors I have worked with in the past have served as my role models. Henry Sun at the Academia Sinica was where I was first exposed to scientific research, and I still blame him for opening the Pandora’s box for me [laugh]. Walid Houry’s lab at the University of Toronto was where I had my first taste of “running an independent project” – and I loved it. I fell in love with Genetics and Developmental Biology when I worked on my undergraduate thesis project in Jui-Chou Hsu’s lab. Joining Kwang Choi’s lab at Baylor College of Medicine was perhaps one of the best decisions I have made. Kwang was extremely supportive and gave me a lot of room and freedom to mature at my own pace. Also Hugo Bellen, who ran the graduate program for Developmental Biology at BCM, who always took a strong interest in my career development and provided much invaluable advice. It was a privilege to work in Elaine Fuchs’s lab for my postdoc training. I was able to truly grow and flourish, and acquired all my “candy shop running skills.”

It’s important to find an advisor that you can look up to. It should be someone you respect, and, perhaps more importantly, someone who can bring out the best in you. However, I am not sure if “finding the right role models” is the accurate description. It is important to recognize that we are all different individuals, and you cannot just find one “role model” and follow an exact approach like following an experimental protocol. Everybody needs to find her or his own recipe.

It’s important to find an advisor that you can look up to. It should be someone you respect, and, perhaps more importantly, someone who can bring out the best in you.

All the advisors I had in the past helped shape who I am today, step by step. They also have different approaches to science and mentoring, which I think is wonderful and enforces the idea that there are many different ways to make things work. What I do is sift through these approaches, identify the ones that fit, and blend them with my personal strengths to make them work for me.